Shortage of bog iron

Having completed the purification of all the sponge iron available to us, we were left with insufficient iron to be able to forge the axe. Removal of slag and the oxidation of the iron surface in the forging process had meant that 5 kilograms of bog iron had been reduced to a bar weighing just over one kilogram. We had to add a few hundred milligrams of iron from more recent times, to make sure we would have sufficient quantities to forge the axe. Two pieces of slaggy iron from a 19th century fence post were introduced, with properties somewhat similar to those of the bog iron. The new iron was forge welded into a split made in the cutting edge part of the axe, so it would be "concealed" in the blade.

Conceding defeat

While we were forging the axe head, a few critical cracks appeared, caused by poor forge welding, as well as fractures caused by pockets of slag. To rescue the situation, we had to resort to modern welding tools, to allow us to complete the forging of the axe. Of course, this was a less than satisfactory compromise.

Rushing, grinding and weight

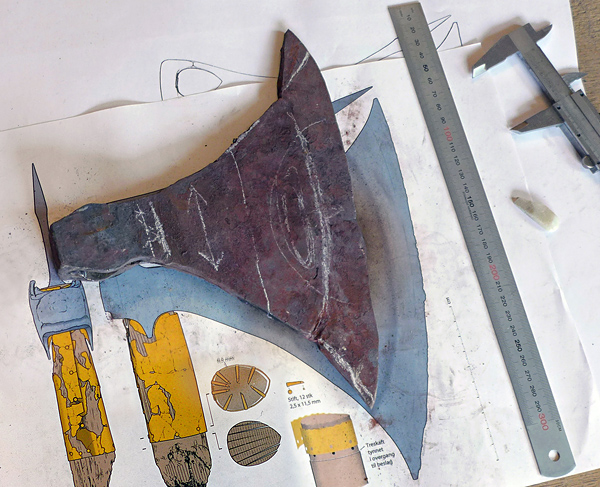

The fact that we were running out of time affected a number of processes. The grinding job had to be brought to an early close, and there was no time to make adjustments. In the end, the axe head weighed approximately 900 grams, much more than the 550 grams of the original axe. On the other hand, the original is heavily corroded, and a calculation of its weight based on the density of corrosion versus metal, suggests that the weight of the Langeid Axe originally could have been c. 800 grams.

We had planned to grind all surfaces of the axe head with a long whetstone made from quartz schist. Sadly, lack of time meant that this could not be achieved. A modern angle grinder had to be used for the rough grinding process, and the whetstone was used mainly on the edge area.

Warping of the cutting edge during hardening

Once the axe had been forged to a satisfactory shape, it needed hardening. This process is always nerve-racking whenever a lot of work has gone into the forging process. A thin cutting edge can easily crack or warp due to the tensions caused by rapid quenching. The hardening process generally went well, but this process freezes the steel into a new structure with a somewhat higher volume. This expansion made the cutting edge longer – its corners curving backwards by almost a full centimetre. Consequently, the profile of the cutting edge became more curved after hardening. In order to re-establish its general likeness to the original, we had to grind down the cutting edge area, thereby reducing some of its length and edge width. The result was that the replica’s cutting edge ended up as one centimetre shorter than that of the original.

Out of doors – too bright

All blacksmithing was done outdoors, often in bright sunshine. This was clearly unfavourable when it came to assessing the temperature of the hot iron. Essential welding processes and the hardening exercise would have benefited from an indoor workshop with even and subdued lighting.