Grave 8 – an ornate sword and broadaxe

In 2011, a burial ground was discovered during archaeological excavations at Langeid in the valley of Setesdalen. This proved to contain several dozen flat graves from the latter part of the Viking Age. Grave 8 was one of the most remarkable. It had substantial post holes in the corners, possibly originally supporting a roof. A wooden coffin was found, but turned out to be almost empty – a disappointment for the archaeologist of course. However, this changed when excavation continued around the outside of the coffin. Along one of its longer sides lay an ornate sword, and along the other a large broadaxe.

Conservation

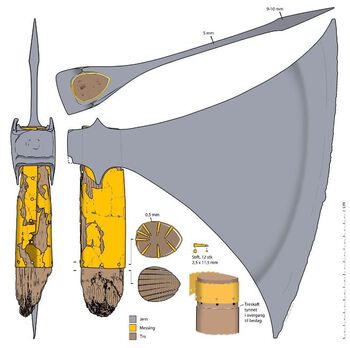

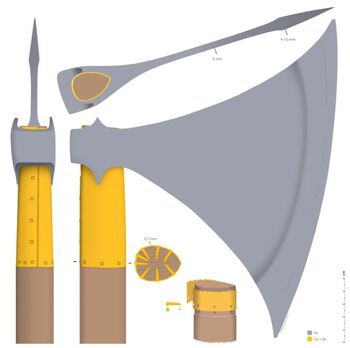

The Langeid axe’s blade was relatively intact, and fortunately the vulnerable toe and heel of the cutting edge as well. Damage to the surface and edges was stabilized and glue was applied before the deposits of rust could be removed by micro-sandblasting. Quite remarkably, parts of the haft of the axe were preserved in the shape of a 15 cm long wooden stump. Before further treatment therefore, the axe was freeze-dried to reduce the risk of the wood shrinking. A band of copper alloy encircled the stump of the haft, and this had preserved the wood. Copper has antimicrobial properties that prevent decay. The copper alloy band on the haft was only half a millimetre thick, heavily corroded and shattered into multiple fragments. These had to be painstakingly glued together.

Shone like gold

A closer examination and the use of XRF analysis (X-ray fluorescence) confirmed that the band around the haft consisted of brass, a copper alloy containing a lot of zinc. In contrast to copper and bronze, which are reddish metals, brass is clearly yellow. Uncorroded brass resembles gold, and this seem to be of importance. The sagas relate the splendour of weapons glittering with gold, clearly an ideal of the Viking Age. However, archaeology reveals that most of these weapons were, in reality, decorated with brass – a kind of poor man’s gold.

The axe gains status

In contrast to the mighty landowners who proclaimed their social standing by bearing a sword as a weapon, less wealthy people resorted to using axes intended for woodworking as a weapon in battle. Thus the axe was often identified with the landless working man, the housecarl (ON: húskarl). This changed somewhat in the latter part of the Viking Age when the era of the broadaxe dawned. This axe, designed solely for battle, might be large, but the blade was thinly hammered and therefore relatively light. The broadaxe gave the Viking fighter a lethal weapon worthy of a professional warrior. Such axe-wielding fighters were regarded with fearful respect, and they were reported to be able to cut off the head of an ox with one blow. They put their stamp on Cnut the Great’s mighty warrior band of housecarls, the Thinglid, and they were sought after all the way to the Mediterranean because of their formidable reputation. In the Byzantine Empire, they served as highly regarded mercenaries in the so-called Varangian Guard, the bodyguards of the Byzantine Emperor. In England these broad bladed axes came to be called a dane axe, due to its use by the conquering danes at the end of the viking age.

The archaeologist Jan Petersen categorized broadaxes as type M in his typology of weapons. Type M appears in the second half of the 10th century and continues into the Middle Ages. The Langeid broadaxe has a slightly later design that ties in with the dating of the grave to the first half of the 11th century. The axe head is large, and with a cutting edge of just over 25 cm and an original weight of around 800 grams (now 550 grams), it is clearly a two-handed axe. Nevertheless, it is lighter than many of the axes intended for woodworking that was put to use as weapons. The haft of a two-handed broadaxe measured around 110 cm, according to the few archaeological finds we have and some contemporary illustrations. This is shorter than many people imagine. The metal banding on the haft is unusual for axe finds in Norway, but there are at least five other examples in the Museum of Cultural History. At the Museum of London they have three brass banded broadaxes dredged from the River Thames.

Gallery

References

- Petersen, Jan (1919): De norske vikingesverd : en typologisk-kronologisk studie over vikingetidens vaaben. Jacob Dybwad, Kristiania.

- Vike, Vegard (2016): "Det er ikke gull alt som glimrer" : bredøkser med messingbeslått skaft fra sen vikingtid. Viking 79: 95–116.

- Wenn, Camilla, Z. Glørstad, K. Loftsgarden (2016): Rapport arkeologisk utgravning Rv.9 Krokå – Langeid, del II: gravfelt fra vikingtid.

- Wenn, Camilla, K. Loftsgarden (2012): Gravene ved Langeid - Foreløpige resultater fra en arkeologisk utgraving. Nicolay 117: 23–31.

- Wheeler, Mortimer (1927): London and the Vikings. London Museum catalogues No. 1. Lancaster House, London.

Project

Video

Read more

- A house for the dead (Langeid grave 8)

- More pictures of the Langeid axe (the museum’s photo database).

- The Langeid sword (found in the same grave as the broadaxe)

- Stunning Viking sword unearthed (MailOnline)

- Broadaxe found in 'death house' at Hårupgård in Denmark

- Invaded by Vikings! (Museum of London)