One of the largest burial grounds in eastern Norway is situated at Veien, north of Lake Tyrifjorden. Archaeologists have been carrying out excavations here for many years. In the 1870s, Oluf Rygh excavated 87 mounds out of the total of 150 then known. Three had already been excavated by amateurs. The burial mounds contained gold and swords, and were dated to the Roman and Migration Period from 0–600 AD. Over a hundred years later, excavations were conducted in the field outside the burial ground. Splendid prestigious buildings were uncovered from the Roman and Migration Period. However, 30 flat graves were also found outside the burial ground and partly under the mounds. In all likelihood, far more lie hidden underneath the mounds. An interesting result from this excavation at Veien was therefore that we discovered a flat grave burial ground that is 1000 years older than the graves in the mounds, dating from the Early Bronze Age around 1000 BC to the start of the Iron Age at approximately the time of the birth of Christ. One of the graves contained a very special iron pin.

What was the reason for the excitement around this simple pin, or fibula as it is also called? The one found in the grave is a La Tène fibula, named after a find-site at Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland, where many finds from the pre-Christian era have been made. Such pins are characteristic of Celtic culture. And hundreds of them have been found in continental Europe, particularly in central and eastern parts.

The flat graves form a sharp contrast to the power display embodied in the buildings and the gold finds: small pits containing burned bones, otherwise nothing at all, or sometimes a few potsherds. Then in one of the graves, a safety pin turned up. This grave, like the others, formed a pit where a vessel made of wood or bark had been placed. Only the birch bark tar that sealed the vessel’s base was preserved in the shape of a ring 30 cm in diameter. The cremated bones had been washed and crushed before being placed in the vessel, and the safety pin lay on the bottom. The birch bark tar is C14 dated to 475–375 BC. There is a source of error in the dating that is difficult to explain. The grave is probably more recent than the dating, possibly from 200 BC.

But a 15 cm long iron safety pin – is that so special? At the time, the earliest iron production had barely started in Norway. Iron was produced by specialists. The method was kept a secret, and iron brought high prestige. We do not know if the pin was made in Norway. At any rate it is identical to the pins worn by people living further south, and it probably came from there.

The custom of cremating the dead and placing the bones in pits at large burial grounds spread across most of Europe. The tradition is called the Urnfield culture because the bones were usually placed in an urn: a pottery or wooden vessel. Not only the burial custom but also parts of the material culture spread to Norway, and artefacts reveal close contact with the Celtic culture area. Although there is only a modest number of objects, they are typical of the period, particularly the fibulas, brooches and belts used with clothing.

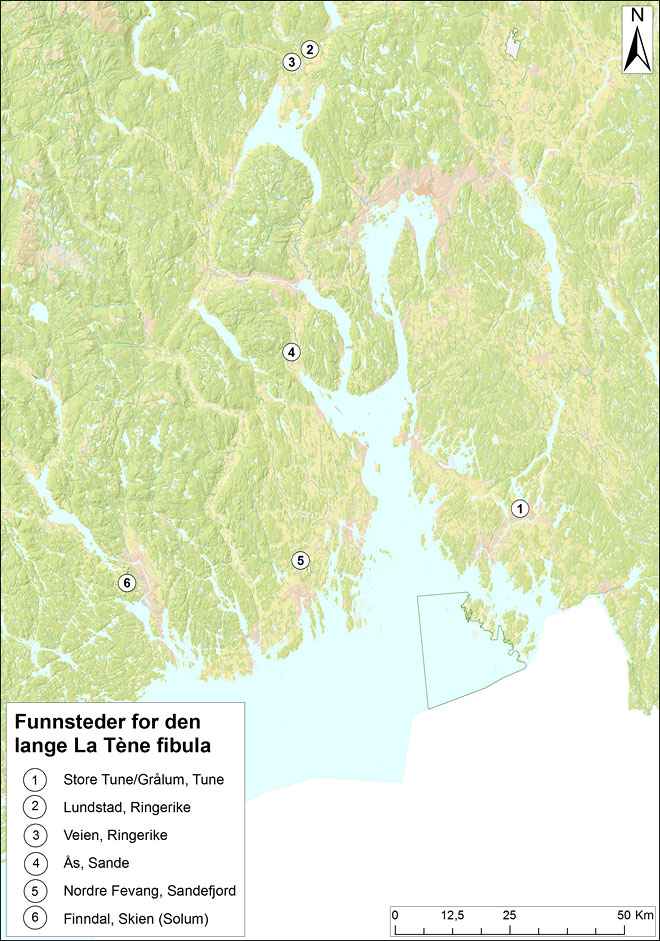

‘The long La Tène fibula’ in Norway

Altogether 23 La Tène fibulas have been found in Norway, all in eastern regions. There are far fewer of the kind that was found at Veien – ‘the long fibula’. It is remarkable that there have been almost no other finds of this type of fibula in the rest of Scandinavia, while they are numerous in Poland and the eastern part of Germany. This suggests a direct link between Eastern Europe and the Oslo Fjord area. Its rarity indicates that the fibula was a sign of distinction, part of high-status attire. The purpose of the pin was to fasten clothing, perhaps a woollen cloak, a particularly valuable garment.

It is worth noting the localities in which this type of fibula has been found. The finds were made in productive agricultural areas around the Oslo Fjord, in places where large burial grounds with rich finds were later established in the Roman Period. These are commonly situated at estuaries or at the arms of fjords joining the Oslo Fjord, with a strategic position in relation to traffic and the transport of goods from outlying areas. Such places are junctions for land and water routes. They were meeting places, social and financial centres where goods as well as ideas were exchanged.

Veien is also situated at a crossroad of large river valleys stretching from Hallingdal and Valdres. From these peripheral areas there is an abundance of game and other resources. During winter, large stretches of both rivers and lakes were passable, but waterfalls posed dangerous obstacles where traffic had to be land-based. Reloading was necessary at the Hønefoss waterfalls near Veien. The overland road passed by Veien, where there were good opportunities to control the merchandise being transported to and from the Oslo Fjord.

The Celts

Burial customs and artefacts found in the Oslo Fjord area show close ties with cultural groups in continental Europe, where Celtic tribes were dominant in the pre-Christian era. Their opponents described them in Greek and Roman sources as being constantly on the move, fighting against each other and taking part in raids. They plundered Rome in approximately 390 BC, they attacked Delphi, the Greeks’ most important shrine, around 270 BC, at approximately the same time as an elderly man, with an iron pin as adornment, was placed on a funeral pyre at Lake Tyrifjorden.

When they covered such distances, is it also possible that they travelled up the Oslo Fjord? Maybe they even reached Lake Tyrifjorden? The word ‘iron’ is probably of Celtic origin. Perhaps Celtic specialists came to

The flat grave burial ground and the iron pin from Veien inspire many questions.

References

Farbregd, O. 1993: Kremasjon – gåtefull gravskikk: Elden, døden og metallet. Spor 1993, nr. 1:8-11.

Gustafson, L. 2016: Møter på Veien - kultplass gjennom 1500 år. Kulturhistorisk museum, Universitetet i Oslo.

Nybruget, P.O. 1978: Førromersk jernalder i Sørøst-Norge. Unpubl. thesis, Magisters degree in Nordic archaeology. University of Oslo.

Nybruget, P.O. og Martens, J. 1997:The Pre-Roman Iron Age in Norway. I J.Martens (Ed.) Chronological Problems of the Pre-Roman Iron Age in Northern Europe. Arkæologiske Skrifter 7:73-90. Copenhagen.

Read more

- Oluf Rygh (archaeologist)

- Pre-Roman Iron Age (Wikipedia)

- The Celts (Wikipedia)