Today as in past societies, meat and animal secondary products (cheese, milk, wool etc.) play an important role in defining patterns of social differentiation. Zooarchaeology - namely the study of animal remains from archaeological sites - represents an invaluable source to reconstruct dietary habits of past communities and to shed light on a variety of historical issues, including social differentiation. Animal remains are indeed associated with food consumption, an important cultural identifier, and are usually recovered in large quantities from archaeological deposits.

Within the FOODIMPACT Project, I analyse the animal bones and teeth recovered from Oslogate 6, an urban medieval site located in Oslo. The main goal of my research is to gain information on food procurement, processing, and consumption habits and, therefore, on potential social differentiation patterns. The Oslogate 6 faunal assemblage consists of more than 1,200 boxes (!!!) containing well-preserved animal remains from mammal, bird, fish and mollusc species; these have been recovered in archaeological context dated from AD 1075 to 1450.

The recording of faunal remains from Oslogate 6 had already been carried out in the 1990’s, and it has been recently digitalised by Head Engineer Olaug Flatnes Bratbak with the active collaboration of Prof. Anne Karin-Huftkammer (University Museum, Department of Natural History - Bergen). The database provides an important starting point for research, and I am currently using it for running the very first preliminary analyses. However, the database misses some information, which are relevant for answering some of the FOODIMPACT project research questions. For this reason, I decided to put my hands on the faunal remains adopting a selective and highly informative recording method. As my post. Doc. is a 2-year project and the material from Oslogate 6 is super abundant, I have decided to focus the zooarchaeological research on cattle, sheep, goat, pig and fish (with a particular interest in cod), as these represent the most important species in the sample. I am going to compare the material from Oslogate 6 with other collections of animal bones. In details, I am looking into these research questions and topics:

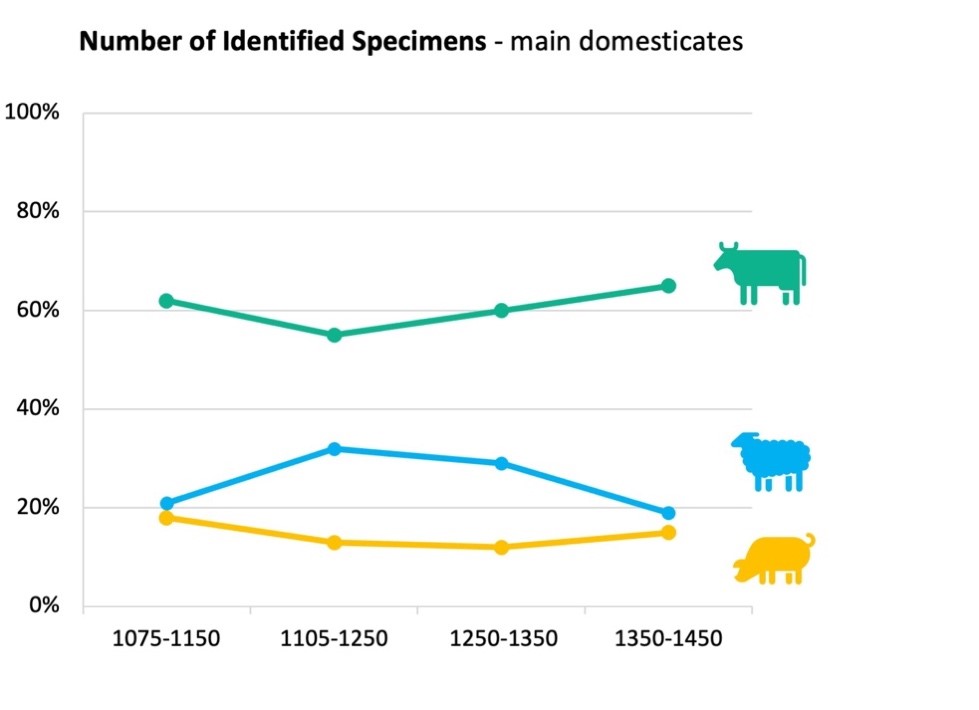

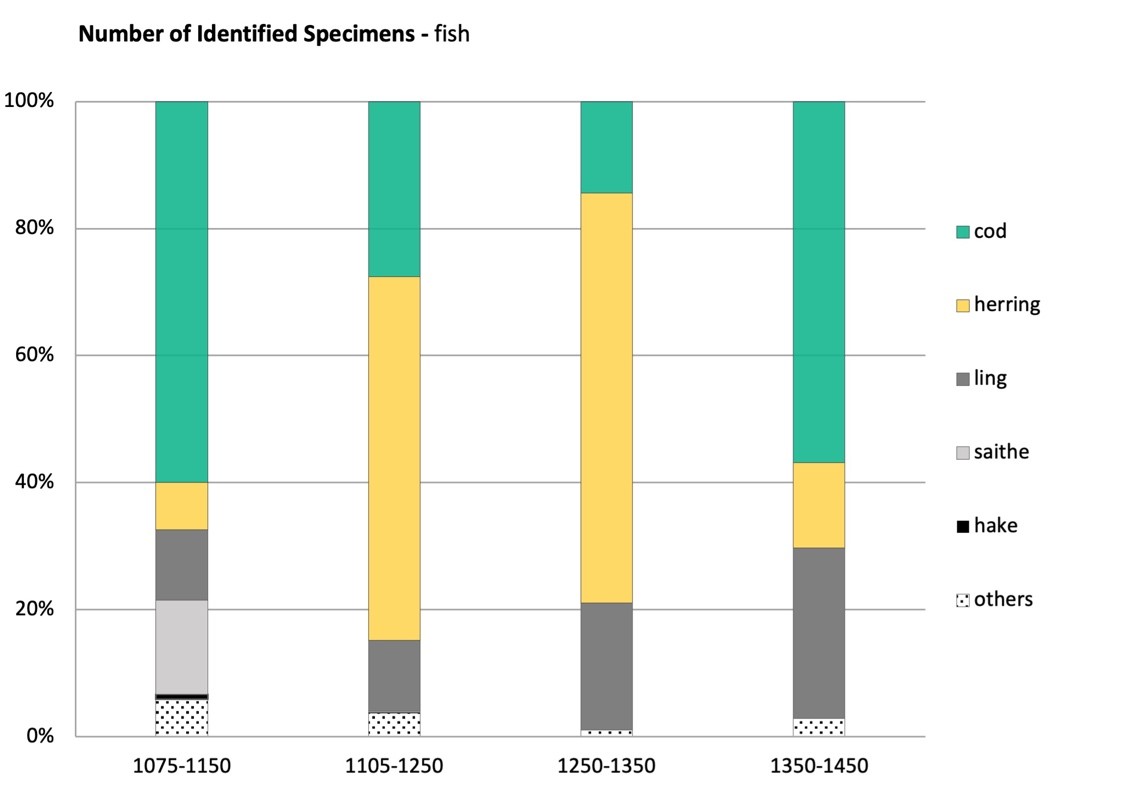

1. Which domestic animal is the most exploited in this period ? ---> By comparing previous and on-going databases, it will be possible to assess - with a higher level of confidence - the frequency of each domestic species trough time. Preliminary analyses suggest that cattle is by far the most represented animal, followed by sheep/goat and pig (Fig.1). Future analyses will corroborate or revise such preliminary hypothesis, and further clarify the reason behind the importance of cattle and other domesticates. As far as fish are considered, cod and herring are the most abundance species; an interesting fluctuation in their representation is visible through time (Fig.2).

Fig. 1. Cattle, sheep/goat and pig - Number of Identified Species from Oslogate 6 in the analysed periods. Fig. V. Aniceti.

2. Was the hunting of wild species a common activity? ---> A comparison of the frequencies of domestic and wild species (red deer, rein deer etc.), and the characters of their remains, will allow to better define the role of hunting activities at the site in the analysed periods.

3. Which animal product(s) people produced/consumed? ---> By analysing both animal teeth (wear and eruption stages) and bones (fusion stages), I will get more information about the outputs sought from animal husbandry by the Oslogate 6 communities. In detail, it will be possible to assess whether animals were specifically exploited for their meat and/or for additional products such as milk, wool, traction force.

3. Which animal product(s) people produced/consumed? ---> By analysing both animal teeth (wear and eruption stages) and bones (fusion stages), I will get more information about the outputs sought from animal husbandry by the Oslogate 6 communities. In detail, it will be possible to assess whether animals were specifically exploited for their meat and/or for additional products such as milk, wool, traction force.

4. Sheep/goat distinction ---> Today, sheep and goat are are usually exploited for different products (often goat is preferred for milk, while sheep for meat and wool). The distinction between sheep from goat remains represents a well-known challenge in zooarchaeology. Following recent methodological advances, I have decided to perform the distinction between sheep and goat using specific morphological criteria, biometrical analyses and, possibly, by looking at peptide sequences in protein collagen (a method called ZooMS).

4. Sheep/goat distinction ---> Today, sheep and goat are are usually exploited for different products (often goat is preferred for milk, while sheep for meat and wool). The distinction between sheep from goat remains represents a well-known challenge in zooarchaeology. Following recent methodological advances, I have decided to perform the distinction between sheep and goat using specific morphological criteria, biometrical analyses and, possibly, by looking at peptide sequences in protein collagen (a method called ZooMS).

5. Butchery evidence and body parts representation ---> by determining how animals were butchered, I will assess the scale of redistribution of resources, e.g., self-sufficiency vs consistent supply patterns, as well as the export/import of specific animal body parts. These analyses might reveal social differentiation patterns among urban areas and periods, the presence of specific butchery areas (where low-quality body parts were discarded) or consumption areas (where selected meaty portions were eaten).

5. Butchery evidence and body parts representation ---> by determining how animals were butchered, I will assess the scale of redistribution of resources, e.g., self-sufficiency vs consistent supply patterns, as well as the export/import of specific animal body parts. These analyses might reveal social differentiation patterns among urban areas and periods, the presence of specific butchery areas (where low-quality body parts were discarded) or consumption areas (where selected meaty portions were eaten).

6. Fish ---> by analysing the presence/absence of specific elements of the cod skeleton and associated butchery marks, it will be possible to assess the presence/consumption of stockfish, and the two ways in which stockfish was (and still is) produced in medieval Norway: the rundfisk and the råskjær.

6. Fish ---> by analysing the presence/absence of specific elements of the cod skeleton and associated butchery marks, it will be possible to assess the presence/consumption of stockfish, and the two ways in which stockfish was (and still is) produced in medieval Norway: the rundfisk and the råskjær.

7. Measuring animal bones and teeth ---> All animal remains will be measured, when possible, by using a digital calliper and/or an osteometric board. Measurements will contribute to reconstruct the incidence of females, castrated and males in cattle and sheep/goat populations, thus providing additional information on husbandry strategies. Measurements will also help at detecting changes in animal size and/or shape through time. A higher demand for meat, for example, would probably have prompted the size improvement of some animals (cattle?), highlighting the will to use herders, as well as the availability of resources, to meet an increased demand for meat.

7. Measuring animal bones and teeth ---> All animal remains will be measured, when possible, by using a digital calliper and/or an osteometric board. Measurements will contribute to reconstruct the incidence of females, castrated and males in cattle and sheep/goat populations, thus providing additional information on husbandry strategies. Measurements will also help at detecting changes in animal size and/or shape through time. A higher demand for meat, for example, would probably have prompted the size improvement of some animals (cattle?), highlighting the will to use herders, as well as the availability of resources, to meet an increased demand for meat.

Fig. 2. Fish - Number of Identified Species from Oslogate 6 in the analysed periods. Fig. V. Aniceti.